![]()

By Loretta Louis

June, 1963

Thirteen miles north of the town of Okanogan on Salmon Creek there is a place that is probably most aptly described as a wide spot in the road. There are two markers to tell the traveler that this was once the site of Ruby City. In all probability, the casual observer might drive through the site of the town without realizing he is on ground once famous as one of the chief mining centers of Washington State, and well might this be true. Scraggly pine trees have grown up on the once Boom Town site and heavy shrubbery is slowly covering the few remaining foundations.

Yet, upon closer scrutiny, the place is unmistakable. Through what was once the center of the town runs a road still in use today. There is little doubt that this road was once the main street of Ruby for there can still be seen faint traces of fully a dozen excavations in a fairly straight line along the road. The remains of several rock foundations may be seen. In a few short years a lively mining town had come into being, lived, and died. More then 114 years have gone by but the famous mining camp has become little more than a legend.

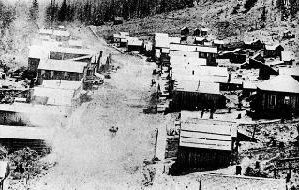

Ruby, Washington-Circa 1894

Ruby City was not the center of the first mining excitement in the Okanogan country, for there were two earlier mining rushes. Later mineral discoveries led to the opening to settlement of Moses reservation March 1, 1886, west of the Okanogan River. As a result of these discoveries the third mining rush occurred and a number of camps sprang up in what is now Okanogan County. There is some doubt concerning the exact time and manner of beginning of Ruby. It is possible that miners had squatted in the vicinity previous to the normal opening of the reservation. Thomas D. Fuller, in 1885, built the first cabin on the site of Ruby.

Following the opening of the Moses reservation the first mineral discoveries were made in the spring of 1886, on Ruby Hill, a steep mountain rising to the height of 3,800 feet above the town. Ledges of quartz carrying silver and a small quantity of gold were found in the country rock of granite and gneiss. John Clonan, Thomas Donan, William Milligan and Thomas Fuller made the original discoveries. They struck a ledge about eighteen feet wide which ran uniformly from wall to wall $14 in gold and silver. Here they located the Ruby Mine. It proved to be the lowest-grade mine on the hill.

The Ruby Mining District was organized by Thomas D. Fuller and others in 1887. First a few claims were staked out. Then, almost magically, more people poured into the town. The late 80’s saw Ruby in its heyday.

Just how rich was the mining district? Was it justified in the claims made for it? Many stories are told of its richness but they are not compatible with the early decline of the camp. Most of the mining was done for silver and a small amount of gold. In the reports of the state geologist the principal mines in the Ruby district are described at length, with much stress upon the great value of the minerals found there. The opinion is given, that with adequate rail communication the Okanogan country would be a second Comstock and would "rival any mineral producing section thus far prospected within the confines of the Union." First and foremost of the mineral districts of Okanogan County ranks the Ruby, located in southern part of the county.

The principal mines and claims on Ruby Hill and near by in the Ruby district (with the dates of location) were: First Thought, Second Thought, Ruby (October, 1886), Fourth of July (April, 1887), Arlington (May, 1887), Butte (June, 1886), Idaho (autumn? 1886), War Eagle, Lenora (September, 1886), Peacock, Fairview, Poorman (October, 1886). Jonathan Bourne Jr. (1855-1940), United States Senator from Oregon 1907-1913, and other Portland mining investors were interested in several of these mines.

One of the principal mines of the district was the Fourth of July. Average assays from the vein showed the ore to be worth over one hundred dollars per ton.

The above information presents pictures that are not easily reconciled. However, it appears that an actual lack of paying ore may have been the principal reason for the sluggish activity at the mines. As is often the case in a mining district, miners and prospectors find it easy to deceive themselves. The miner is the most hopefully optimistic of people. Such was the case in Ruby City. People were not finding the rich veins they expected. In spite of this, they continued to work the mines until a combination of forces caused the decline of the district.

Rubyites, in the strong belief of what the district had to offer, were not timid in imposing that belief on those who would listen. In reality, Ruby was only a small camp perched on the side of a mountain where mines were being worked with varying degrees of fervor and success. The bumptiousness so characteristic of the camp is plainly shown in the few remaining copies of the town’s one newspaper, The Ruby Miner. An advertisement in the issue of June 2, 1892, which takes up some four out of the six columns of the four page newspaper, asserts that:

As Virginia City is to Nevada so is the town of Ruby to the State of Washington. Ruby is the only incorporated town in Okanogan County. It is out of debt and has money in the Treasury. Public schools are open nine months every year, under the management of competent instructors, thus furnishing unsurpassed educational advantages. Let us make some money for you in Ruby. This district is appropriately termed the "Comstock of Washington." Nature has endowed Ruby with elements of a city. Man has supplied the adjuncts to make a metropolis.

Not only was the mining population concerned with the advent of more and more people into the town of Ruby, it planned to build another town close by. In the Ellensburgh Capital for July 24, 1890, the following item appears:

A new town has been laid out in the Okanogan country and named Leadville. A force of men are now employed in clearing the brush and timber off the streets. It is located on a beautiful site about four miles below Ruby in the Salmon River Valley, through which the company will build their line of railroad to connect with the Washington Central at the Columbia River.

No accounts have been found to show that this second Leadville ever developed beyond the townsite stage.

The youthful enthusiasm which characterized Ruby was not alone in advertising the district. Curiosity brought many visitors, and there is direct evidence that some of these were favorably impressed. Again in Ellensburgh Capital it is found that:

The prediction is freely made that it will equal if not exceed Leadville (Colorado). Mr. Ad Edgar, the veteran stage man is also full of enthusiasm over the mines and predicts a glorious future for that region. He thinks that there will be one fine city and several splendid towns in that section and a wonderful influx will be witnessed as soon as the country is tapped by a railroad, which it now seems will be the case inside of two years. When a railroad reaches the Okanogan look out for a Boom, so say all who have visited the mines.

Rubyites realizes that transportation by freight wagon and light rig was not particularly helpful in developing the district. As the railroads extended their lines farther into the state, the promoters of Ruby made efforts to secure a branch line which could run close to the mines. Time and time again throughout the newspaper articles of this period there is mention of railroads, coupled with the belief that the day was not far distant when Ruby would receive rail service. That day never dawned for Ruby.

When it is realized that the Ruby district was not tapped by a railroad, the question arises concerning transportation into and out of the camp. For some time after the town was established no regular means of transportation was in existence. Of course, freighters made trips to the various supply stations, Ellensburg being one of these. Its importance in this capacity came about in part because Ellensburg men did much to promote the town of Ruby and surrounding mines. This information is gained from the diary of the late Austin Mires of Ellensburg, who made a number of trips to Ruby during its period of highest development.

Ellensburg and Ruby were but four days apart by team and buggy. From Ruby the trail dropped down the Salmon Creek to the Okanogan River at the Francis Jackson ("Pard") Cummings ranch, where the present town of Okanogan stands, or led over the Chiliwist, more to the southwest. The next stop was at the ferry to Foster Creek, where Bridgeport was located, across the Columbia River. From this ferry the road led down the Columbia to Waterville. After dropping down through Corbelay Canyon, the Columbia was reached and recrossed where Orondo is now situated. Then the road ran down the west side of the river as far as Wenatchee. The last part of the journey was the crossing of Coluckum Pass and a ride into Ellensburg.

It is interesting to note just what made up the freight coming into the new country. According to a man who made a number of freighting trips to Ruby, sugar, flour, coffee, bacon, and syrup made up a large part of the provisions brought in. Other necessities were miners tools, clothing, and liquor.

Spokane, Cheney, Sprague, and Coulee City, the terminus of the Central Washington Railroad, were also distributing centers. For a time the higher grades of ore were freighted by team to Sprague, terminus of the Northern Pacific Railway, and shipped from there via Spokane to the Tacoma smelter. When the railroad reached Coulee City, the ore was hauled there and shipped to smelting centers. Before the stage line was established in 1888, settlers at Ruby used to make up a purse to send a rider to Sprague for mail, at a charge of ten cents a letter. The stage road, the only means of communication with the outside world, ran from Coulee City, terminus of the Central Washington Railroad, to Penticton, British Columbia, at the foot of Okanogan Lake. It struck the south bank of the Columbia River at Foster Creek (Bridgeport), where the road divided. One branch crossed the Columbia there by ferry, traversed the southwest corner of the Indian reservation, and crossed the Okanogan River by ferry about seven miles above its mouth.

The other branch continued along the south bank of the Columbia and crossed the river by ferry at the river port of Virginia City. About ten miles above the mouth of the Okanogan the two branches of the road reunited at Ophir. Near Alma the road left the Okanogan and ran up the canyon of Salmon Creek to Ruby, thence six miles to Conconully. From Conconully it ran over to and down the Sinlahekin and Similkameen, via Loomis, to Oroville, where it struck the Okanogan River again and ran north to Penticton

There were few good roads in the county. When mining districts were close enough together, the miners endeavored to build roads between camps. Such was the case between the towns of Ruby and Lomiston (Loomis). The Ruby Miner of March 2, 1892, made a plea for the completion of a road between these two towns. Most of the road, apparently, had been built. The Ruby Miner contended that "this leaves a gap of only about three miles to build, and if the citizens of Ruby will raise three hundred dollars in either money or labor, this piece of road can be completed in thirty days." Here again is noted that sluggishness which was mentioned earlier.

Three hundred dollars is not a large amount to raise in a thriving mining town, but such was the case in Ruby. The paper concluded its plea by asserting that "by the middle of April (we) should have one of the best roads in Okanogan County, between its two principal towns." Ruby did at least contract for grading of its main street in the summer of 1892. Even four years before (1888), Austin Mires had written in his diary: "Salmon City (Conconully) is located better than Ruby and is now a more thriving town."

In summing up the story of transportation in the Ruby mining district, it can be said that the first roads were merely trails through the tall bunch grass. These trails later developed into well-traveled roads, which may or may not have followed closely the original trails. Efforts were made to build roads from the steamer landings on the Columbia to the mines, between the mining districts, and within a particular district. The Ruby mining district and the others surrounding it never had satisfactory roads.

The town of Ruby was typical of other small mining camps. One of the better descriptions is given by Guy Waring:

Ruby, in 1888, was at the height of its power. Miners and prospectors were flowing there from all over the Northwest, and more than a thousand men and women inhabited the town, which lay for a quarter of a mile along a single graded street, built up solidly on either side with stores and mostly log houses.

Available photographs show a predominance of frame buildings in the camp, rather than those of the log-cabin type.

Visitors in the town did not always find the accommodations desirable. On the occasion one of his trips to Ruby, Austin Mires related in his diary:

![]()