![]()

When David Thompson Passed Through

By R.H. Mansfield

Pioneering was a rugged business, and the earliest pioneers were more concerned with survival than keeping records for future historians to study. The life of the natives was an almost equally strenuous effort to stay alive, and they made no written records. As a result, a positive answer to our opening question cannot be given. But, from such records as are available, the members of the North West Fur Company expedition led by David Thompson, who began the descent of the Columbia River at Kettle Falls (Ilthokayape) on July 3, 1811. And, who paused in route during the morning of July 5 to visit the tribe they knew as "Inspaelis" (Nespelem), and again paused on July 6 to visit the "Someethhow" (Methow) natives, get credit for being the first in Okanogan County.

There is no doubt that the men of that task force, together with the men of the Pacific Fur Company expedition who emerged from the opposite direction a few weeks later. These men put in motion the activities that brought this area into the consciousness of the American and British authorities, and originated commerce and other contact with the inland native people.

Publicity associated with the founding of the Fort Okanogan Museum has made many people aware of the basic facts of the Pacific Fur Company (more commonly called the Astor Company) and its beginnings than with those facts of the slightly earlier Thompson led group. So, it may be interesting to tell first some of the story of the latter, with special emphasis on the Okanogan County aspects of it.

Since 1790 men of the North West Company had been promoting expansion of activities to the Pacific Ocean. Alexander McKenzie broke through the Bella Coola in 1793, but not with economic success. Lewis and Clark made their exploration in 1804-1806, putting the United States in the overland race, but without trading. Simon Frazer made his way to the ocean in 1808. Contributing the knowledge that the Fraser River was not the Columbia River as he and McKenzie had believed, and was not a feasible trade route.

In 1810 John Jacob Astor chartered his Pacific Fur Company with the avowed intent of entering the fur trade on the Pacific Slope by way of the Columbia River, with headquarters on the ocean. The North West Fur Company partners were aware of this threat of competition. In fact, Astor had told them of his plans and invited them to join in a common undertaking. But they refused, choosing to compete. They sent directions to Thompson, who was even then on his way eastward to Lake Superior, to return and proceed down the Columbia to its mouth to resist the establishment of the trade by the Americans. Thompson and his men had been in the headwaters of the Columbia River since 1806, and were south of the 49th parallel of the latitude and west as far as the mouth of the Little Spokane River (site of Spokane House) by 1810.

Thompson reached the upper Columbia (near the site of the Mica Creek Dam now in construction) with only three men in midwinter of 1810-1811 but could travel no farther until April. Then he went southward and westward along his established routes (up the Columbia, down the Kootenae, overland to the Clark's Fork, and down the Pend Orielle) recruiting a crew for his intended trip from among the employees and free traders associated with the established fur trade of his company.

His crew was completed at Spokane House, and they traveled northwesterly overland to Kettle Falls where they met with the Indians and spent about two weeks, the time needed to build a single large cedar canoe for the journey down river. The crew consisted of Thompson, Michel Beaudreau, Pierre Panet (or Pariel), Joseph Cote, Michel Boullard, and Francois Gregorie, all French Canadians. Charles and Ignace, Iroquois Indians, and two unnamed "Simpoil" (San Poil) Indians, recruited as interpreters, who stayed to help them until they arrived at Crab Creek on the night of July 7.

A minimum of trade goods was carried for use in obtaining provisions. By late afternoon of the first day, after embarking at 6:30am, they reached the San Poil River where they paused to fraternize with the Indians camped there. It was a year of unusually high water, and the rapids, eddies and whirlpools had caused Thompson difficulty in reading his compass. But he enjoyed the scenery, refreshing to it in his journal as a country that "always wears a pleasing romantic view".

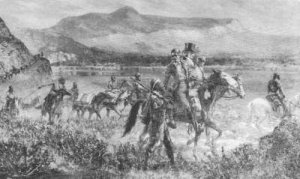

Each spring a Hudson's Bay Company brigade of 200-300 horses delivered beaver pelts from central and northern British Columbia (then known as New Caledonia) to Fort Okanogan. The brigade is shown (in about 1825) passing Lake Okanogan with the chief factor wearing finery and a tophat to impress natives. At Fort Okanogan, the furs were loaded into double-ended bateaux for a voyage down the Columbia River to western headquarters at Fort Vancouver.

He was not so pleased at the sight of the Indian camp, finding it dirty, so they went upstream a quarter mile to make a separate camp. The evening was spent in making friends with the Indians who were not in the least troublesome, except to keep them from an early retirement by talk and dancing. They learned all they could of the country, staying until noon the next day.

During the afternoon of July 4, 1811, their canoe entered what is now Okanogan County, and Thompson noted the existence of "fine low lots" in the vicinity. They saw no people, and pressed on, beyond the "Pass of the Black Tailed Deer" almost due west of Buffalo Lake, and about seven or eight miles downstream from the spot on which Grand Coulee Dam now stands. Passing "very fine meadows on the south and entering the Box Canyon where Ignace, one of the Iroquois, accidentally struck by an over hanging drift log, fell overboard. In spite of his inability to swim, he stayed afloat long enough to be pulled back into the canoe.

This accident happened as they were working their way down the rapids after carrying their goods around. They had enough for the day, and set up camp on the "rude stones" for lack of a better place. Here Thompson bled Ignace that evening. Because their experiences in this place had made such an impression, it was known there after as "La Rapide d'Ignace". They shot two geese this day and broke two paddles. Although they saw no one on July 5th, they had traveled only a little way the next morning when they met the "Inspaelis" or Nespelem Indians, about 60 strong, with their chief, who made them gifts of horses, roasted salmon, arrow wood berries, and two bushels of various roots. They had experience with roots before, and declined the Ectooway roots, which produced colic. They also declined four small, dried, fat animals assumed by them to be marmot. In payment for what they kept, they gave three feet of tobacco, fourteen rings, eighteen hawks bells, one fathom of beads, one and one-half fathom of gartering, four papers of paint, four awls and six buttons.

These Indian people described the country downstream as far as the Okanogan River (less then fifteen miles away). The travelers smoked with and talked to the Indians and were entertained by Indian dances. Thompson noted that the land was poor, bearing grass in tufts of a round hard kind, and two kinds of strong scented shrubs with white leaves. The women were "tolerably well clothed", the men "rather slightly". They used ornaments of brilliant white shells as bracelets, as armbands, in the hair, on their garments, and about the head, and David Thompson was favorably impressed by their appearance. As one who had spent two-thirds of his forty-one years among Indians throughout the northern half of the continent, his reaction constituted a high compliment. With the exception of a few copper ornaments worn by women, no mention was made of any metal implements. None of the men was "lusty" (it is assumed this is a synonym for large, or tall), but almost all were well proportioned and some were "well looking". The women were of all sizes, none corpulent, and with one exception, none "handsome". They were able to understand his Iroquois interpreter, but he was unable to understand their dialect of the Saleesh language, and it required help from one of the San Poils who understood both.

First fur trading post at the mouth of the Okanogan River was a 16-by-20-foot cabin built of driftwood by a small party from John Astor's Pacific Fur Company in the fall of 1811. The Astorians had paddled up the Columbia from its mouth. So amiable were the local Indians that usually only one man was assigned to winter here.

No mention was made of the pattern of life of the Indians here, save references to their use of a native tobacco plant, not yet ripe, and their use of salmon and roots and berries for food. It is not likely that their customs and activities differed greatly from those of the other Indians in the region.

However, one may assume from the absolute lack of comment in the journal to the contrary, that these Indian people were entirely peaceable and committed no acts of theft. It is recorded that they performed a ritualistic prayer dance for the safety of the expedition.

After spending the night here, the Thompson party set off again about 6:30am on Saturday, July 6th and because of brush or for some other reason, they missed sighting the mouth of the Okanogan River. And, by 10:00am arrived at an encampment of Indians near the mouth of the Methow River, which they called the "Smeethhowe" Indians. This place was about two and one-half miles upstream from the Methow Rapids. It is not possible to tell exactly where this stopping place was, but it seems certain it was at or near the former Francis Adams orchard tract.

A near repetition of the events of the day before took place, and the Indian men and women smoked with them. This seems to have been the method employed everywhere with Indian people to establish a friendly atmosphere for conversation. On this occasion it was recorded that although each man took from three to six puffs from the calumet, the women were permitted only a single whiff each. The intention to explore the river to the sea, and thereby open a trade route whereby the Indians could obtain merchandise, was explained, and the Indians wished them success. As before, the Indians could tell them of the condition of the river only as far as the next tribe. The usual presents were exchanged. At noon they went on, obtaining help by horses and men to transport them around the Methow Rapids, in a little more than one hour.

A short while later they passed beyond the southerly tip of Okanogan County. At 2:30, near Chelan Station they saw a sheep; one of the crew, a man named Michel, set out to shoot it, but was unsuccessful. A few minutes later, probably while pursuing the sheep, they killed two rattlesnakes.

This expedition traversed the length of the Columbia River with the same dispatch. They paused wherever Indians were found, to make friends and to promise a return with trade goods. At the mouth of the Snake River they fastened a notice to a pole, claiming the country for Great Britain and announcing their intent to erect a trading "factory there". They know this to have been the Lewis and Clark entry to the Columbia River, and they observed in the possession of the Indian chief near they're the Jefferson Medal he had received from the explorers. Thompson and his crew arrived at Astoria at midday on July 15, just as the Astor party was about to begin its trip upriver to the Okanogan country. The Thompson party had learned on July 10, near John Day River, that the ship of the Astor Company had already arrived at the mouth of the river.

Notwithstanding their rivalry, the two groups were cordial and spent a week together. Then, on July 22, all of Thompson's party, joined by the expedition that was shortly to found Fort Okanogan for the Astor people, started back up the Columbia River. They traveled together, in part for protection from the Indians along the lower falls of the Columbia who had been very belligerent and troublesome to all passing people. On July 31 they arrived at The Dalles, where, because their lighter load permitted Thompson's party to travel much faster, the two groups parted company. Thompson changed his plans for travel, and instead of proceeding up the Columbia, he turned east up the Snake River as far as the mouth of the Palouse, then overland northward back to Spokane House. They arrived on August 13, and so they did not again touch Okanogan country on that trip.

The next non-Indian people of record to enter Okanogan County were these same Astorians who left behind at The Dalles by Thompson, laboriously worked their way up the Columbia to the mouth of the Okanogan River. The members of this party were David Stuart, the leader, Clerks Ovide' De Montigvey, Francis Pillette, Donald Mc Lenman and Alexander Ross. Two or three Canadian voyageurs whose names have not been established, two Hawaiians, or Sandwich Islanders and two Kootenae women on their way home. These eleven or twelve people traveled in two dugout canoes obtained from the Chinook Indians, very slow and clumsy craft for river travel.

As they passed the place now known as Priest Rapids, they took into their employ a medicine man of a resident Indian tribe who became the wrangler for the horses they bought along the way. He remained with them until they stopped at the Okanogan. This party entered Okanogan County during the day of August 28, spent the night of August 29, and the day and night of August 30 at the mouth of the Methow River, just opposite the town of Pateros, presumably on the land that until recently was the Mel Chapman orchard.

The same friendly Indians who had visited the Thompson party there a few weeks earlier gathered to greet the Astorians, and tried to persuade them to stay and trade through the winter. One might almost think of this as being the "New Industries Committee" of the Methow tribe in action. They lost the bid, in any event, for the expedition went on, entering the Okanogan River that was ascended for about two miles (to the Carden ranch, or Bonar ranch, or their about) for their night's camp.

Indians followed them along the shore, camped with them, and continued to importune them to settle among them. Mr. Stuart held out for a time to test their sincerity, but, once convinced, and after receiving the promise, following a council of the chiefs. (From this we may assume it was a joint undertaking of an "Okanogan County Council of Indian Tribes") that they would:

1. Always be friends of his people,

2. Kill plenty of beavers for them,

3. Furnish them provisions at all times, and

4. Insure their protection and safety,

He agreed. This was the original treaty made between Indians and whites in the Okanogan country. This treaty bears little resemblance to the "treaty rights" talked of today. One wonders, whimsically, if it might be enforced, or if damages might be claimed for failure of the Indians to perform the solemn promises of their forefathers. The expedition then retraced its way to a site about one-half mile upstream from the Columbia and on the flat between the two rivers where they pitched their tents and commenced to build Fort Okanogan.

Stuart, with Montigvey, Michel Boullard, and another of the Astor expedition first traversed the Okanogan Valley. Who, as soon as the original building at the Fort Okanogan was put together, went north by way of Okanogan River and Lake Okanogan, then westerly over the hill to the site of Kamloops, B.C., where they made arrangements for future trading with the Indians there. They then returned to Fort Okanogan, arriving on March 22, 1812.

During their absence, four men had returned by boat to Astoria, and Alexander Ross was left alone to operate the business during the winter. He was surprising successful, obtaining 1,550 beaver pelts, worth 2,250 pounds sterling on the China market, in barter for merchandise costing Mr. Astor about 35 pounds.

The first white man in the Similkameen River area seems to have been this same Alexander Ross who, having gone to Kamloops in late 1812, returned by a new route, apparently by the Nicola Valley, then to Princeton area and so down the Similkameen and back to the Okanogan.

Ross seems also to have been first into the Methow Valley, penetrating in 1814 to the Skagit in an effort to reach tide water, but lacking in complete success. So far as may be established by documentation, the foregoing tells us the story of the first penetration by whites and other non-Indians into the Okanogan. There are a few speculative possibilities that are of interest, however, and some future research into sources not now available for study may prove that David Thompson was the first to pass this way.

For example, there is the matter of the letters delivered by Indian messenger to David Thompson. Back in 1807, during Christmas week after the founding of his Kootenae House on the Columbia headwaters, a letter dated September 29, 1807 signed "Jeremy Pinch Lieut", and purporting to be from a U.S. Military officer arrived there. It referred to specific rules and regulations promulgated by Americans for trading with Indians, and had been written from a place called Poltito Palton Lake.

Alexander Ross, originally in charge of the post at Fort Okanogan.

Thompson thought it genuine and from an exploring party, but dismissed the matter with a reply saying he was referring the matter to his company's partners. The Pinch letter referred to a previous notice received by Thompson at Kootenae House prior to September 23, 1807. Also, by Indian messengers, issued by James Roseman, Lieutenant, and Zachery Perch, Captain and Commanding Officer, from "Fort Lewis, Yellow River, Columbia", dated July 10, 1807, setting forth rules for trading with Indians.

Many historians believe that these messages were the devious work of Manuel Lisa who followed up the Missouri after the Louisiana Purchase with a party of that size, but not beyond the east side of the Rockies, and who originated trade with the Indians there. The Indians had told Thompson that they received the message from an U.S. military expedition of forty-two men at the confluence of the "two most southern and considerable branches of the Columbia", and that the expedition was proceeding further down river. If there was such an expedition of that size, as close as the mouth of the Clearwater River, it is not impossible that a party from it could have entered the county within Okanogan County.

Another, and much more likely, prospect of an earlier explorer into Okanogan County would be from among the people within or associated with the North West Fur Company itself. Whenever an advance westward was made by the company, "free-traders" went along or followed immediately behind. These were people who by experience knew the business, and although not on the payroll, they were helpful in the trade. There were several of these in the Columbia watershed from 1807 on, and they could easily, especially by 1810 when Spokane House was founded, have entered the Okanogan country. If they did, the business records of the North West Fur Company might so show, but these have not been available for study.

The North West Fur Company employees might also have previously been in the Okanogan country. Thompson made annual trips east with furs and to bring trade goods, and while he was so employed, he left people such as Jaco Finley and Finan McDonald in charge. These were very enterprising and energetic people, not reticent about making explorations on their own. These are, it is believed, the two people responsible for closing down the Saleesh House in Western Montana and moving to Spokane House at the mouth of the Little Spokane, in 1810.

It does not appear in Thompson's journal or his narrative account, but one historian has written that Finan McDonald and Pierre Legace were in residence over the winter of 1807 with an Indian chief near the site of Spokane, and each took a daughter of the chief. It would have been quite possible, between 1807 and 1811, for either of these men to enter the Okanogan.

There is a diary entry for June 17, 1811, made by David Thompson at Spokane House while preparing for the trip down the Columbia to the "Teck a ner gons" (Okanogan), indicating that people at Spokane House were aware of the geographic area of the Okanogan. The famous map of the western part of the North American continent made by David Thompson during 1813 and 1814, after he had left the West in 1812 never to return. This map shows an amazing amount of detail, mostly accurate, of the Okanogan country, and it is hard to believe he learned it all on his one trip through. A logical and probable source was the employees and free hunters.

Judge William Compton Brown, in his study, concluded, "Thompson and his party were undoubtedly the first to reach this part of the Columbia". And, referring to the brief sojourn at the mouth of the Methow, he says, "these Indians along here had already become quite well acquainted with white men. This acquaintance almost certainly came through North West employees and associates.

Thompson had been reared and educated in a London charity house. He apprenticed to the Hudson's Bay Company at age 14, taught himself mathematics, and learned surveying during winter isolation at a prairie trading post. His Chippewa wife Charlotte and three children often accompanied him on his travels.

![]()