![]()

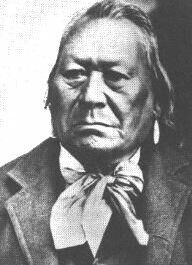

Chief Moses, Sulk-stalk-scosum - "The Sun Chief"

Compiled by Jerry Smith

Chief Moses, Born 1829,

Died March 25, 1899,

Aged 70 years

His childhood name was Loo-low-kin (The Head Band). Upon coming of warrior age his name became Que-tal-li-kin (Blue Head Horn). In later life he took the name of his famous father, Sulk-stalk-scosum, (Piece split from the Sun), "The Sun Chief." In all his dealings with the whites he always proudly cherished the name of "Moses." He was the chief of the Sin-kah-yous or Middle People throughout the last forty years of his life.

Chief Moses attained greatness because he came to realize his band of Columbias would have to adjust to the coming of white men. The chief would have waged war if he thought he could win. But a trip to the east in 1879 convinced him the United States was to powerful. The following are quotes from Chief Moses. Chief Moses to an Indian agent on the Okanogan River, 1870: "I fear the ruin of my people is coming." Chief Moses once told a follower to count the grains in a pile of sand. "There are too many," said the man. "It is the same with whites," replied Moses, "There are to many." Chief Moses to "Okanogan" Smith, November 1891: "I want to have a little fun before I die."

Chief Moses respected the army, which treated him as an individual, but disliked the Indian Bureau because he felt it looked on all Indians as a collective group of savages.

Chief Moses, leader of the Columbias, lies buried near the Indian Agency in Nespelem, 2 ½ miles south of town.

The Moses Reservation

By Dr. Robert H. Ruby

All of present Okanogan County was at one time in Indian reservation. That part east of the Okanogan River is the Colville Reservation. That part west of the river was part of an area proclaimed on April 18, 1879, as the Columbia Reservation for Chief Moses and his tribe, the Columbias. The Secretary of the Interior opened a "bee hive" in giving these Indians the land bounded on the east by the Okanogan River. And the Columbia River from the mouth of the Okanogan to the mouth of the Chelan River; south along the latter and Lake Chelan to the summit of the Cascades; and west along the Cascade summit to the Canadian border. The latter formed the north boundary.

Approximately the same bounds formed a mining district organized in 1860 by the Okanogan (sic) and Similkameen Mining District. After the United States Mining Laws of May 10, 1872, had been adopted by Congress, declaring mineral deposits free and open to exploration, occupation and purchase. Then giving exclusive right to possession and enjoyment to the locator. The district residents met on the Fourth of July 1873, and drew up articles of by-laws after reorganizing as the Similkameen Mining District. At a January 2, 1874, meeting the name was again changed, this time to the Mount Chopaka and Similkameen Mining District.

Immediately, on learning their district had been given to Moses, the miners met on July 9, 1879, near Lake Osoyoos and drew up a set of resolutions:

"Agreeable to notice a meeting of those persons owing property located upon the Reservation lately set aside for Chief Moses was held on July 9, 1879 at Toads Coulaugh (sic) so called."

"Meeting called to order by H.F. Smith who was elected Chairman and E.D. Phelps Secretary. The Chairman stated the object of the meeting to be to secure appraisers to appraise the improvements of the Settlers many of who do not wish to remain if the country is made an Indian Reserve. Motion made and carried that a committee of three be appointed by the Chair to draft resolutions expressive of the sense of the meeting."

"Palmer, Johnson and Granger were appointed (sic) said committee. Meeting adjourned to await report called to order by Chairman and the following resolutions read and adopted and committee discharged." (sic)

"Resolved, that we the residents upon the proposed reservation set apart by a Proclamation of the President for Chief Moses are opposed to its being set apart for a reservation. On account of its mineral resources and its effect upon the farmers and stock raisers causing great expense and inconvenience of running stock as under the present state of affairs there is no place known where to move with safety.

"Resolved, that in the event of its being made a permanent reserve we ask that there be appraisers appointed to value the property and that one shall be a thorough mineralogist and Geologist and the other practical men acquainted with the value of property and expense of moving the same.

"Resolved, that we respectfully ask that a Commission of Geologists and Mineralogists be appointed by the Government to examine the mineral resources of the proposed reserve before it is definitely set apart as an Indian Reservation.

"Motion made and carried that a copy of these proceedings be sent to the Secretary of the Interior also that H.F. Smith be appointed to wait upon the Governor of Washington Territory and present the matter to him for his respectful consideration.

"Motion made and carried that a committee be appointed to secure the signature of those persons owning property upon the proposed reserve to the proceedings of this meeting W. Granger appointed on said committee meeting then adjourned."

The resolution was signed by H.F. Smith Chairman, E.D. Phelps Secretary, T.S. Moore, R.L. Johnson, W. Granger, James Palmer, D.S. Gillett, Daniel Driscol, Slick McCauley, W.S. Williams, Robert Clayton, G.W. Runnells, George Sutherland, A.R. Thorpe, Dan Tillison and John Bell.

It ended: "A true copy attest E.D. Phelps"

Hoping to keep the Indians out of their "bees' wax," Hiram F. "Okanogan" Smith sent to the Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz, a copy of the hastily drawn resolutions. The conflict of interests in the area as a complete surprise to the "red faced" Schurz who passed the papers on to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, E.A. Hayt, with the wish that the miners would suffer no wrong.

Pressures brought to bear over the next three years on Congress to restore the land were of atomic force. Fearing the loss of energies already invested in the locations, some 26 recorded locations and relocations prior to April 18, 1879, the miners dared not add to their improvements. The U.S. District Attorney for California was locating new claims during this time in spite of a precedent-setting opinion in 1864 that no mining claims are allowed on a military establishment. The Interior Department yielded the job of administering the Columbia Reservation to the War Department since Moses would not accept Interior supervision by an agent. The miners wanted reimbursement for their improvements if they could not have their mines.

With the establishments of the Moses Reservation, the military located a camp at the south end of Lake Chelan where it could keep a watchful eye on the Indians. Moses complained to the military officials of the settlers on his reservation; the Great Father, the President, had promised to keep whites out. Colonel Henry C. Merriman, the commander, sent Captain H.C. Cook north on August 19, 1880, to enumerate and determine the value of improvements on the reservation and to ask the owners to "pack up" and leave. Those he found at home were Alvin R. "Albert" Thorp, George "Old George" Sutherland, Robert "Old Bob" Clayton, James Palmer, George W. "Tenas George" Runnels, Thomas G. Moore, and Alexander "Alex" or "Slick" McCauley. Cook valued these peoples' improvements at $3,577, considerably less than $11,000, the total of their own estimates.

Presumably Cook also contacted Smith, who lived just off the reservation on the east side of Osoyoos Lake. Smith sent a letter to Cook stating he was replying to his interrogation "in regard to the value of the silver mines located in pursuance of an Act of Congress, passed May 10, 1872 on Moses Reservation, so called and owned conjointly by" Marshall Blinn, Phelps, Henry Wellington and Smith. Smith claimed their seven mines had a prospective value of 10 million dollars.

While the military emissary did not dispose of the reservation intruders with snap of the quirt ease, the presence of those who paid him lease money disturbed Moses very little. The miners, most of whom were investors living elsewhere, were determined to get back the mineral rich land in the northern part of the reservation. Late in the summer of 1880 President Rutherford B. Hayes, accompanied by General W.T. Sherman, visited the northwest and learned first hand of the error the government had made in giving Moses lands on which miners held claims. Hayes was apologetic and asked Territorial Delegate Thomas H. Grents to assemble and present to Congress information on the problem. Mining people asked the President to restore the land to the public; good suggestion, thought Hayes, which if properly representative of the people, could result in an executive order for the same.

The miners were busy as bees as they went about to regain their "hives." That December when Congress convened Brents was ready with his presentation. At the same time Dr. Thomas T. Minor, a civic minded physician in the Pacific Northwest, suggested to Schurz that a five to ten mile strip of reservation along the Canadian border be turned back to the whites. Practically all-mining locations were within ten miles of the boundary.

Miners circulated numerous petitions, one to the effect that they are allowed to obtain title to their claims, another that a ten-mile strip be shaved off from the Indian land and saved for them. Washington territorial Governor Elisha P. Ferry notified Schurz of the "ten mile strip" petition. On December 19, 1880, officials of the Eagle Mining Company wrote General Sherman that a petition had been sent to delegate Brents and requested the general's influence. Attorneys were hired to lobby Interior officials. Delegations visited Washington, D.C., to contact lawmakers first hand.

With pressure on government officials at the bursting point, the Interior department officials decided to negotiate with Moses to purchase a strip of land. Colville agent John A. Simms, whom Moses did not like, was designated contact man. Knowing that the potentially explosive matter would have to be settled in some manner and soon, General Miles, whom Moses respected, sent A.J. Chapman to the chief independent of the Interior's investigation to ascertain the chief's feeling in the matter. With the information he gained, the general agreed that to prevent war, a part of Moses' reservation should be purchased by the government so it could be returned to those who claimed ownership and opened to others wanting to locate thereon.

The military determined there were seventeen valid residents prior to April 18, 1879. They were Runnels and two of his son-in-laws, one Tooler and Moore, Johnson, Clayton, McCauley, Dan Griswold, John McDonald, Thorp, Palmer, Henry Melner, Sutherland, John Paxton, Henry Vincent, Smith, C. Rinharte and William Leach.

Smith, kingpin of the miners, continued to alert the Secretary of the Interior with messages and suggestions, which were becoming bolder. On September 19, 1881, he asked that a fifteen-mile ribbon be cut from the reservation and placed back in the public domain. He suggested a portion of the south end of the Colville Reservation (already given to other tribes) be traded to Moses for the fifteen miles. The miners had help from Okanogan Indian Chief Tonasket, who favored selling a part of the reservation, and giving the money to ALL Indians, not just Moses. Even some of Okanogan Chief Sar-sarp-kin's people came out in favor of opening up the area to miners who made a ready market for garden products these Indians raised.

Governor William A. Newell, speaking to the Eighth Biennial Washington Territorial Legislature on October 5, 1881, spoke in favor of abolishing reservations and opening the land for settlement. Moses and his people were naturally disturbed and uneasy over the grabby attitude of anxious whites.

With a rumor that the Government might lease portions of the reservation, a meeting was called for the mining district members on December 1, 1881, at which time they drew up resolutions. The miners complained that the military had advised the miners and settlers to abandon their homes and property. Cook had valued their property at considerably under estimates of those living on the land. Runnels had been taken under escort to the military camp (recently moved from Lake Chelan to the mouth of the Spokane River) for refusing to obey the military. The land was given to Moses after they located mines on the reservation, the Surveyor General of Washington Territory refused to survey their claims. Moses and his band did not occupy the area, less then than one hundred Indians lived on the area. The reservation policy of the Government was a "failure and a farce;" but demanded that if leases were granted they should be general. They asked to be paid a just value for their improvements if forced to abandon their mines, providing the property was not opened for occupation and settlement. They asked that the Secretary of the Interior appoint a commissioner to appraise the property and a geologist to make a report of mineral resources. That no settlers are arrested for expressing views of the U.S. Army to its officers. That the Surveyor General appoint someone to survey the claims located prior to the proclamation setting up the reservation so mine owners could get titles for patents as provided by law. That the government vacates and declare the land open to exploration, or such portion as "it may deem advisable for mining and other purposes." And that the government authorities permanently locate Moses and his band on the Colville Reservation. "Provided the Government persists in its pet folly of establishing and maintaining reservations for Indians." The resolutions also called for allotting the Indians in severalty with exemption from taxation.

The declaration that Moses did not live on the land given him was correct. The first winter after being kicked out of the Columbia Basin, he and his people holed up in the Kartar Valley on the Colville Reservation. After that he wintered for a couple years near the mouth of the Nespelem River and finally in the Nespelem Valley where he located permanently.

The situation became more acute through the next year. Hal Price, then Commissioner of Indian Affairs, could stand the pressure no longer and suggested on August 1, 1882, to the Secretary of the Interior that an inspector be sent to council with Moses to get him to relinquish the mineral rich strip of his reservation. Inspector Robert S. Gardner was sent from Washington, D.C., to the Colville Agency to confer with Moses. Patrick McKenzie, squawman and agency interpreter, rode out from the agency to Moses' camp to bring in the chief, who refused to come because one of his wives, a daughter and brother were sick with smallpox. (Moses' wife and brother died.)

Mary Moses, wife of Chief Moses

Nonetheless, Gardner went about his assignment, interviewing numerous people in the area of the fifteen mile strip heard from whites about the restoration soon after it became law, and suffered the worst possible insults from disrespectful whites who then ran over Indian property, destroying it. General Miles feared an Indian uprising, so angered were the natives. In short the principals signed order, Moses and other chiefs were taken to Washington, D.C., where, after conferences, an agreement July 7, 1883, for the Government to purchase the entire reservation from the Indians. For those formerly assigned to the Moses Reservation to remove to the Colville Reservation or remain on the former and be allotted if they so choose.

By act of Congress on July 4, 1884, the entire Moses Reservation was restored to the public domain. It was May 1, 1886, before the area was officially opened for white entry and settlement. The influx of people was so great that Okanogan County, which includes a large chunk of the former Moses Reservation, was split from Stevens County and became an entity unto itself two years later.

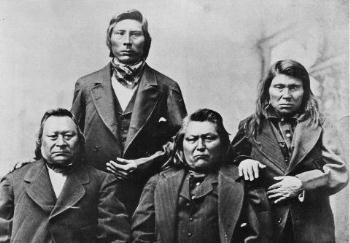

Four Indian leaders in Portland, Oregon, in 1879 before departing for Washington, D.C. From left, Chief Moses, Jim Chil-lah-leet-sah (a nephew of Moses), Chief Peo-Peo-Mox-Mox, and Kah-lees-quat-qua-lat

![]()